TIME IS MORE VALUABLE THAN MONEY

STOCK MARKET

If some ninety-year-old rich dude offered you $100 million to trade places with him, would you do it? Of course not. Why? Because time is more valuable than money. The average person has approximately 25,000 days to live in their adult life. If you’re reading this book, you likely need to trade your time for money in order to live a life that is safe, healthy, and happy. But if you didn’t have to work to make money, you’d be able to spend that time however you wanted. No one cares about your time as much as you do. People will try to take your time and fill it up with meetings and calls and more meetings. But it’s your time. Your only time. This book is designed to help you make the most of it. Make money buy time. The goal of this book is to help you retire as early as possible. When I say retire, I don’t mean that you will never work again, only that you’ll have enough money so that you never have to work again. This is complete financial freedom—the ability to do whatever you want with your time. I don’t ever plan to retire in the traditional sense of the word, but you could say that I’m “retired” now because I have enough money and freedom to spend my time doing whatever I want. I no longer have to work for money, but I still enjoy making money, and it’s attached to many of the things I enjoy doing. I love working and challenging myself and hopefully always will, so checking out to a life of leisure just isn’t my vibe. If you want to “retire” sooner rather than later, you need to rethink everything you’ve been taught about retirement and probably most of what you’ve been taught about money. As a society, we have collectively adopted one approach to retiring: get a job, set aside a certain portion of your income in a 401(k) or other retirement account, and in forty-plus years you’ll have enough money saved that you can stop working for good. This approach is designed to get you to retire in your sixties or seventies, which explains why pretty much every advertisement about retirement shows silver-haired grandmas and grandpas (typically on a golf course or walking along the beach). There are three major problems with this approach: 1. It doesn’t work for most people. 2. You end up spending the most valuable years of your life working for money. 3. It’s not designed to help you “retire” as quickly as possible. We’ll start with the first problem. To illustrate why traditional retirement advice doesn’t work, I’d like to introduce you to Travis. Travis is an old friend of my parents, so I’ve known him for a long time. Back in 2012, when I was already well into my quest to become a millionaire by thirty, I ran into Travis at a holiday party thrown by another family friend. While schmoozing with the other guests and snacking on Virginia honey ham in my festive holiday jacket, I struck up a conversation with Travis, who had heard (via my parents) that I was thinking of starting a business. Travis and I typically see each other only once a year at this holiday party, so he had no idea that I’d made almost $300,000 in the past year by pursuing a whole bunch of opportunities: building websites, running ad campaigns, flipping domain names, selling mopeds, and various other things. “So you want to be an entrepreneur?” Travis said. “Pretty cool, man. But it’s going to be pretty tough at first. It always is for entrepreneurs. You’ve got to make sure to save some money. I’ve been saving five percent of my income for retirement since I started working, and I’m planning to retire in the next ten years.” Travis was about forty-five at this time and had been working for twenty years. I asked him how he had decided to save 5 percent of his income for retirement back in his twenties. “Oh, back when I first started out,” he said, “a coworker of mine told me I should start saving that much, so I did.” I was speechless. By this point I had read hundreds of books about investing and personal finance, and I knew that, despite his confidence, Travis was probably never going to be able to retire, let alone in the next ten years. I don’t have access to Travis’s financial statements, so it’s possible he has some savings, income, or assets that I don’t know about, but let’s assume all he has is his income and whatever he’s set aside for retirement since he entered the workforce. Travis is a project manager at an energy consulting company. I don’t know what he takes home, but according to websites like PayScale and Glassdoor, he probably makes about $60,000 a year. Even though I don’t know his exact salary, I know a lot about what Travis spends his money on because my parents have known him for a long time. In the past three years, he has bought a new house (for at least $500,000), redone the kitchen and put an addition on the new house (for at least another $150,000), and bought not one, but two new cars. By outward appearances, the dude is living like a king, but based on what he’s likely earning, he’s probably living on an insane amount of credit to afford this lifestyle, even when you factor in his wife’s income. She works in a similar role and likely makes about the same amount of money as Travis. Neither Travis nor his wife come from money, so a big inheritance to offset their spending is unlikely. Let’s take a quick look at the numbers. If Travis has been saving 5 percent of a $60,000 annual salary, that means he’s saving about $3,000 per year. Even if he’s been making $60,000 a year since he was in his mid-twenties (which is unlikely, since incomes usually rise over time), he would have set aside only $60,000 total by now ($3,000 × 20 years = $60,000). If he’s invested that money in his company’s 401(k) and his company has matched the standard 3 percent of his contribution over that period, he’d have an additional $36,000 saved, for a total of $96,000 (3 percent of $60,000 = $1,800 × 20 years = $36,000). Thanks to the magic of compounding (see the box below), any contributions he’s made will have grown for as long as they’ve been invested. We can’t know exactly how much his 401(k) would be worth without knowing what specific assets (i.e., stocks or bonds) he has invested in, but we can be fairly certain that it’s worth more than his original investment.

Compounding accelerates money growth and will make you richer

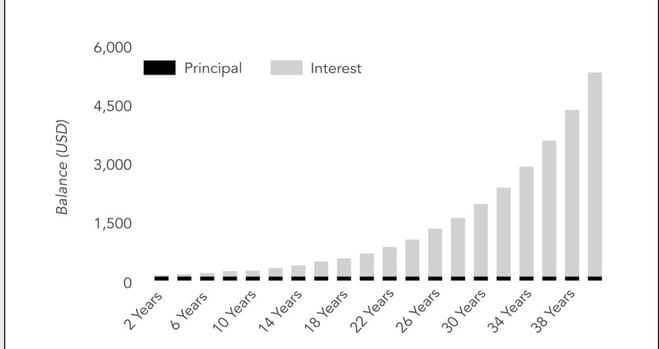

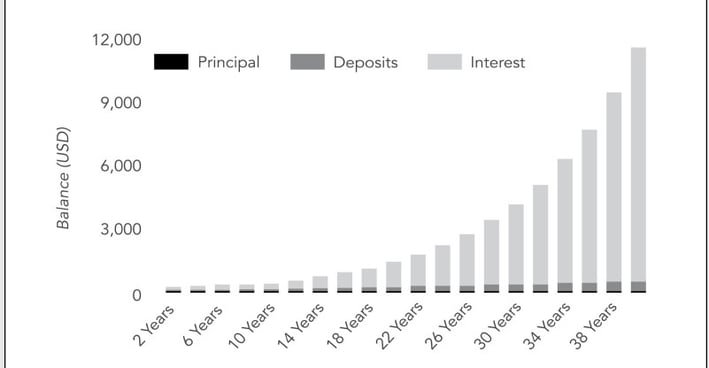

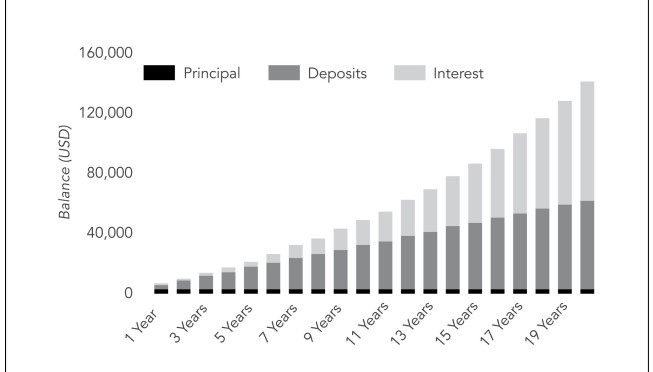

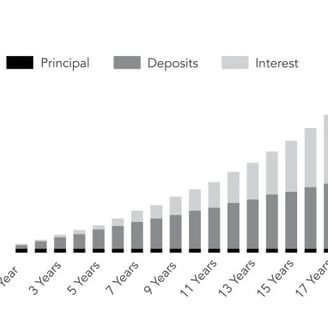

There is a reason Einstein is said to have called compounding “the eighth wonder of the world,” because it’s so amazing. Compounding exponentially increases the value of your money over time, even if you don’t increase your investments, because your interest grows interest (aka your money keeps making more money). The key to fast-tracking financial freedom is to speed up compounding by making and investing as much money as early and frequently as you can. Here’s how it works. As a stock goes up, the value of any money invested in that stock increases by a certain percentage. The growth is known as interest. If the stock keeps going up, then both your original contribution and the past interest keep growing. Over time, the more money you invest and the more the interest grows, the faster your money compounds. It looks like a curve, as you’ll see in the graphs on this page. Of course, the earnings (or losses) of the stock market can vary wildly from month to month and from year to year, but over the long term, many economists have found that the real dollar returns (meaning returns adjusted to account for inflation and stock dividends) of the U.S. stock market average between 7 and 9 percent per year. However, when it comes to estimating potential stock market returns, it’s better to be a bit more conservative, so for this reason, I’ll be using 7 percent as the estimated stock market rate of return throughout the course of this book. For the sake of simplicity to illustrate the impact of compounding, let’s say the market grows by 10 percent in a given year. If you invest $100 and it grows by 10 percent, you will have $110 at the end of the year (10 percent of $100 = $10; $100 + $10 = $110). If the market grows by another 10 percent the following year, you will earn 10 percent not only on your original $100 investment but also on the $10 return you earned the previous year. This means that at the end of the second year, you would have earned an additional $11 (10 percent of $110 = $11) for a total of $121. This is the one of the craziest thing about money and compounding: $1 or 1 percent might not seem like a lot, but it can have a massive impact on how much money you have over time thanks to compounding. To illustrate, let’s look at what happens to that $100 if we keep it invested at 10 percent annual growth for forty years, without adding any more money to it

Yes, that’s right. That original $100 investment (aka your principal) will be worth $5,370 in forty years, and you didn’t even contribute any additional money to it! That’s a 5,270 percent increase! If you continue to add to your principal (which is what you typically do when investing for retirement, since you invest more at least every month), that money will be worth even more. Even if you add only $1 per month to your original $100 contribution, you’d have deposited a total of $480 over 40 years, but it would be worth $11,694! Awesome!

If Travis has been saving $3,000 per year, and that money has been growing at the average 7 percent annual rate (see box, this page), he would have $142,348 after saving for twenty years. This is certainly a lot of money, but it’s not enough to live on if he plans to retire by fifty and lives into his seventies or eighties. And this assumes he was smart and put his money in a total stock market index fund, which tracks the performance of the entire stock market and is therefore most likely to generate the average 7 percent return over time. If he didn’t, he would most likely have even less saved.

I don’t mean to pick on Travis. In fact, most Americans approach retirement the same way he does. As of 2016, the median household income in the United States is $57,617, and the average American is saving only 3.6 percent of their income per year. That means the average American household is saving $2,074 per year—even less than what we assumed Travis is saving. As mentioned in the last chapter, the average millennial is saving between 3 and 5 percent of his or her income, which, based on the average millennial income of $35,592, equals about $1,067—$1,776 per year. For simplicity’s sake, let’s round that up to $2,000 a year. Saving $2,000 per year growing 7 percent per year equals $470,967 in forty years. While $470,967 is a lot of money, keep in mind that due to inflation, which is unpredictable, $470,967 likely won’t have the same purchasing power in forty years that it does today.